إذا سألت رمزي البعلبكي: لماذا ندرس اللغويات، فـلن يـجد عناءً في الإجابة. يقول البعلبكي، الحاصل على جائزة الكويت لعام 2021 من Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences (في مجال الإنسانية والفنون والأداب — علم اللغويات): “اللغوياتُ أمرٌ حيوي لفهم البشر ومجتمعاتهم، فهي مرتبطةٌ بالحياة والتواصل وكيفية تعامل البشر مع بعضـهم بعضًا” البعـلبكي هو أستاذ اللغة العربية في الجامعة الأمريكية ببيروت، لكن حتى طــلبـة اللـغـة الـعـربيـة في الجــامعـات الأخرى سيعرفون اسمه، فهو مؤلف مشارك للقاموس الإنجليزي– العربي الشهير، المورد Al-Mawrid.

Baalbaki’s love for the Arabic language started early. His father, Mounir Baalbaki, was one of the most influential translators of Arabic of his time. Among the books he translated from English were many important works of history, religion, and politics as well as world literature. The author Taha Hussein, who was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature twenty-one times, called Mounir Baalbaki “Shaykh al-Mutarjimin al-Arab” (The foremost Arab translator). “I remember that as of the age of 10 or so, my father used to take me on walks and recite to me lines of Arabic poetry and alert me to the beauty of Arabic and its ability to express the finest shades of meaning,” said Baalbaki, who also learned from his father to spend long hours at work every single day.

Balbaaki himself focused on doing research in two major areas of Arabic linguistic study, namely, the Arabic grammatical theory and the Arabic lexicographical tradition. He studied at the American University of Beirut before obtaining a doctorate from the University of London in the United Kingdom. He has published 10 authored books on Arabic Grammatical Theory and Arabic lexicography as well as six critical editions and studies of classical Arabic texts, four edited volumes, and more than eighty single-authored articles, which appeared in some of the most prestigious journals in the field. In 2010, Baalbaki won the King Faisal International Prize for his contribution to the study of Arabic grammar. He was only the third Lebanese person to be awarded this prize since its inception in 1979.

The renowned Al-Mawrid dictionary was started by Baalbaki’s father. “He worked on it for fifteen years but passed away before completing it, so I took it upon myself,” he said. It took him six more years before, what is now known as, the most comprehensive English-Arabic dictionary was published. Its more than 2,100 pages include thousands of updated entries for modern Arabic, such as technical terms in technology, communications, and medicine.

But Baalbaki was also instrumental in proving that Arabic linguistic studies and its two main branches, namely grammar and authoring dictionaries, are authentically rooted in the Arabic-Islamic culture itself. It used to be thought that the study of grammar and the idea of dictionaries were brought in through foreign influences, possibly from the Greeks or the Syriacs. Baalbaki helped show that this wasn’t true. “The early classical Arabic sources link the beginning of the grammatical activity to the efforts at understanding and properly interpreting the text of the holy Quran,” he said. “The sources report several anecdotes that demonstrate that early grammatical activity began in response to errors that were made in reciting the Quran. In other words, the grammarians were keen on protecting the Quranic text from linguistic corruption.”

To this day, grammar is related to Islamic law, the Quran, and the traditions of the Prophet, according to Baalbaki. “For example, a judge who is ignorant of grammar cannot render a correct verdict related to divorce. The judge should distinguish between a man who divorces his wife by saying: anti taliq taliq taliq (three times) and one who does so by saying anti taliq wa-taliq wa-taliq (by using the conjunction waw, meaning ‘and’),” he said. “In the first case, the divorce was pronounced once but emphasized by the repetition. But the second statement means that the divorce took place three times. Any judge who doesn’t understand such grammatical issues is bound to make faulty verdicts, which can affect people’s lives.”

The interconnectedness of language and society is one reason why linguistics is such an important field of study in Baalbaki’s eyes. “As an interdisciplinary field, it is hardly matched by any other field in humanities and social sciences. Sociolinguistics focuses on the relationship between language and identity and things like gender issues related to language,” he said. “Other branches of linguistics are psycholinguistics, historical linguistics, dialectology, and more recently, neurolinguistics and computational linguistics.”

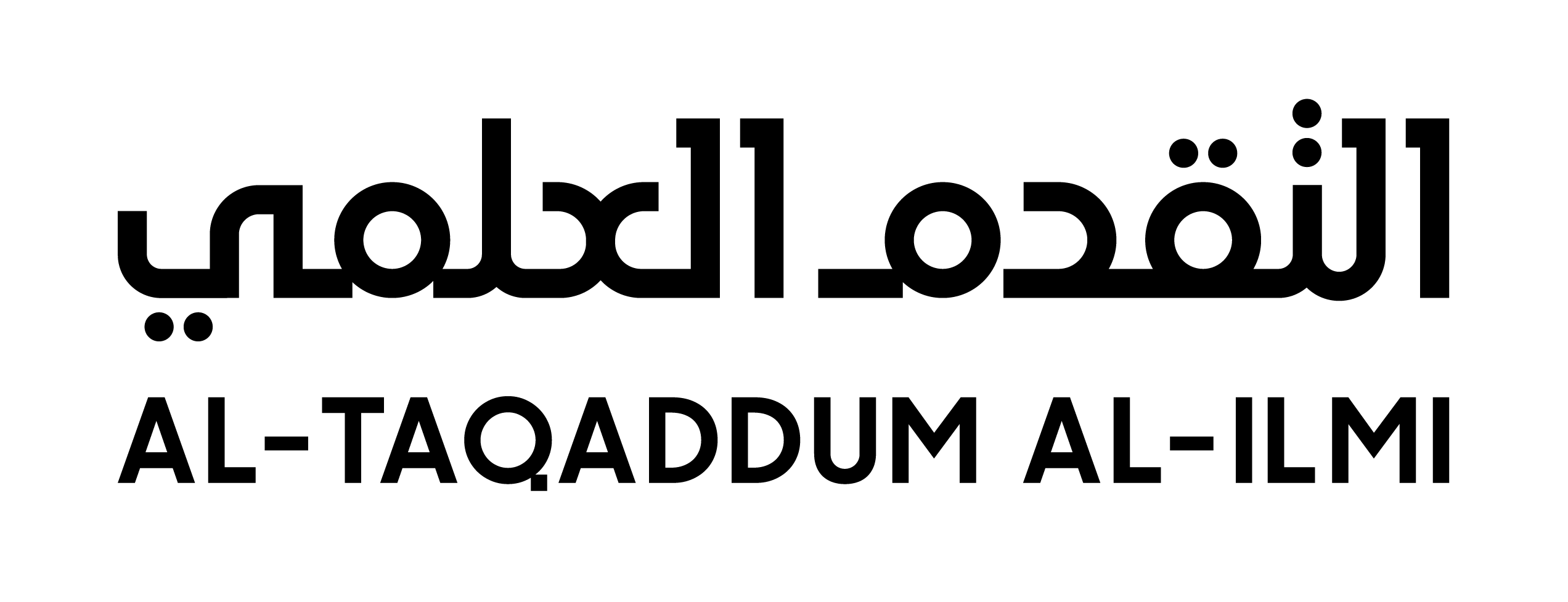

At 71 years of age, Baalbaki isn’t ready to slow down just yet. In 2011, he proposed a historical dictionary for the Arabic language to the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies in Doha, Qatar. It’s an ambitious project that has been tried – and has failed – several times since the 1930s. But under Baalbaki’s leadership, some 300 university professors, linguists, and scholars from Jordan, the United Arab Emirates, Tunisia, Algeria, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Iraq, Palestine, Qatar, Kuwait, Lebanon, Egypt, Morocco, Mauritania, Yemen, and other countries have now started to track every Arabic word from its earliest occurrence in inscriptions and texts. The first entries of the historical dictionary were published online in 2018. Baalbaki estimates that the entire project might take at least 15 years before it will be completed. This doesn’t faze him. “The passion for my research and my students is what keeps one going in life,” he said.

He appreciates how important KFAS’ Kuwait Prize is to the field. Established to support scientific research, innovation, and creativity and given annually to distinguished Arab scientists who have made outstanding achievements and contributions, the award “is recognized as one of the most prestigious prizes in the Arab world,” said Baabaki. “Undoubtedly, it has given Arab scholars an added incentive to produce and disseminate knowledge.”