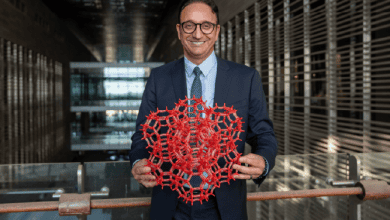

Some materials carry such obscure names it prevents non-scientists from understanding their importance in everyday life. One such example is the perovskite, the yellow, brown, or black mineral that looks like a diamond. Perovskites are used to make solar cells, which are electronic devices that derive energy from the sun and convert it into usable electricity. “These materials can be made at low temperatures using simple and easy chemistry, and helps us make imaging of X-rays affordable and protect the patient from risks like that of cancer because we don’t need to administer high doses of radiation,” said Osman M. Bakr, a professor of materials engineering and science at the Department of Physical Sciences and Engineering at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) in Saudi Arabia. “The big picture is for perovskite solar cells to facilitate the lives of people around the world who cannot access proper medical diagnostics,” said Bakr, who has coauthored 155 peer-reviewed papers and been cited numerous times in the most respected scientific journals, leaves great promise for healthcare.

Born in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1981 to an engineer father, Bakr learned from a very young age the importance of education, science, and high ambition. Upon finishing high school, he went to the U.S. to study material science and engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where his father had also studied. In 2003, he embarked onto his doctorate in applied physics at Harvard University. The journey from MIT to Harvard was short: “I just took the subway and two stops down the road I exited,” he said. True, studying at two Ivy League universities equips you with a powerful and broad knowledge of materials physics, materials chemistry, and access to stellar mentors and lab work–all these helped Bakr grasp the importance of materials to civilization and humanity. But it also forges your personality.

“اعتدتُ على أن أكون طالبًا جيدًا حقًا في الـسـعـوديـة”، قال بـكر. وأضاف: “في مــعـهـد ماساتشوستس للتكنولوجيا، كنتُ أجلس في فصل دراسي الجميع فيه طلبة استثنائيون، وكـنت مجرد طالب عادي”. وما يثير الاهتمام هو أنه وصف تلك التجربة بأنها كانت مريحة إلاّ أنها مُحررة للفكر، ومحفِّزة إلى أبعد حد. قال: “أدركتُ أنه حتى لو لم تتمكن في بعض الأحيان من الحصول على درجة مثالية، فأنت ما زلت متفـوقًا”. في الـوقت نفسه، “كانت أهمية وجود أشخـاص من حـولك يدفعونك إلى مستوى جديد تمامًا أمرًا محفِزًا للإدراك … تبدأ ببلوغ مستوى لم تدرك وجوده من قبل. … الدراسة في معهد ماساتشوستس للتكنولوجيا تشبه أن تتمكن من الصمود أمام سيل هائل ينهال عليك. إذا تمكنت من النجاح في هذا الوسط، فهذا رائع. هذا يجعلك أقوى”.

Harvard was smaller, but more interdisciplinary, according to Bakr. “You could select the courses you want and work with anyone you want, so I tailored my education,” he said. Interdisciplinarity is all the rage today–and for a reason. Bakr shared his dormitory with a student in German literature, a student doing his graduate degree in architecture, and another one specializing in public health. This exposure to people from all walks of life and specialties afforded him a perspective of the world he might have missed hanging around engineers only and immersed him in the bigger issues of society. “I understood I could use the innate curiosity, analytical thinking, and problem-solving skills I had as a scientist to deal with problems belonging to social sciences; look at how researchers are using AI to analyze language and address public health issues,” Bakr said. “It’s a good example of how society’s problems can be addressed using solutions first seen in science and engineering.”

That said, living in the U.S. in the early aughts was not all rainbows and sunshine. From an all-boys school in Saudi Arabia, Bakr was transplanted into an environment with all sorts of diversity. Even the weather was different. He arrived in Cambridge, Massachusetts a year before 9/11. After that day, Bakrfelt he had to run the extra mile to make sure people felt comfortable with him instead of lumping him with whatever stereotype they had in their head. Fast forward 21 years, and 20,954 Saudi students study on scholarship in the U.S. Back then, there were only a handful though. “It was not very common to encounter someone from Saudi Arabia at the graduate level. 9/11 aside, people were also genuinely curious as they didn’t know much about us,” Bakr said

He speaks fondly of Saudi Arabia and the generous and supportive scholarship programs it provides. His own academic trajectory was supported by a government scholarship. “Even before KAUST was built, they [the Saudi government] set up the King Abdullah Scholar Award, a competition sponsoring ten graduate students from around the world to continue their research efforts,” Bakr said. “Mid-way in my doctorate, I applied and won the award,” And he decided to give back to his country by choosing to stay and conduct his research in it– research that has already blazed a trail. Metal nanoparticles are these practically invisible, tiny, and metallic particles with a metal core and organic shell that are today known to possess remarkable electronic, optical, and chemical properties. “How do they form? What will happen if we put them inside the body? If we subject them to light, how will they react? These are common questions people asked back then,” Bakr said. “We spent years trying to prove they even existed.”

By Ivy Lockett