The Noninvasive Future of Health Monitoring: Dina Katabi’s Journey in Engineering and Medicine

How artificial intelligence (AI) and Wireless Signals Are Transforming Healthcare

“Invisibles is a non-intrusive way to track health. EQ-Radio has the potential to transform environments based on a person's mood” Dina Katabi

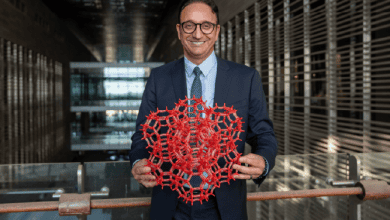

تستطيع المهندسة الكهربائية دينا القتابي أن تقول بحق إنها تُحدِث ثورة في الطب بصفتها أستاذة دكتورة ثوان ونيكول فام في معهد ماساتشوستس للتكنولوجيا. تعمل القتابي على دمج الذكاء الاصطناعي وتكنولوجيا الحاسوب في تطبيقات تحويلية تستهدف الأمراض الخطيرة والرفاه العاطفي العام للسكان. يستخدم أحد مشاريعها البارزة، إنفيزيبلز “Invisibles”، إشارات لاسلكية لمراقبة العلامات الحيوية وحركات الشخص من دون الحاجة إلى أجهزة قابلة للارتداء. تساعد Invisibles المرضى الذين يعانون حالات تنكسية عصبية مثل مرض باركنسون وآلزهايمر (تنطق آلزايمر)، إضافةً إلى اضطرابات المناعة الذاتية مثل مرض كرون والذئبة، من خلال تتبُّع تطور الأعراض واكتشاف العلامات المبكرة. كما يُعد مشروع إى كيو-راديو EQ-Radio مشروعاً رائداً آخر من مشاريعها. يستخدم هذا المشروع إشارات لاسلكية للكشف عن مشاعر الشخص من خلال تحليل معدل ضربات قلبه وأنماط تنفسه – تخيل أليكسا متقدمة للرفاه العاطفية.

“Invisibles is a non-intrusive way to track health. EQ-Radio has the potential to transform environments based on a person's mood. Imagine your home playing your favorite music when you're stressed or changing the lighting to suit your mood,” Katabi said, who is also the Director of the MIT Center for Wireless Networks and Mobile Computing at the MIT Computer Science and AI Lab.

Circa 1997, the Syrian academic embarked on her PhD. She had dreams of making the internet—still in its infancy back then—more efficient by improving WiFi and wireless networks. Her foundational research led her to develop innovative wireless sensors capable of sensing location and movements entirely wirelessly. From this, Katabi’s research evolved to creating biosensors that could detect biological and physiological signals, marking the genesis of her pioneering projects described above. The medical and wellness fusion of AI and medicine is not only the logical progression of Katabi’s postdoc work at MIT; it also made her parents, especially her father, a cardiologist who staunchly opposed her becoming an engineer, “very proud.”

When Katabi told her parents that she wanted to quit medical school to switch to engineering after spending a year in med school in the mid-1990s, “everyone in the country was shocked.” Growing up in a family of physicians in Damascus, Syria, it was only expected that she would follow the same path. The best students typically go to medical school in Syria--it was a one-way street. “What, you want to be a researcher? That is not even a job,” everyone said. To suddenly drop med school after having topped the class in the first year and move to something that is “lower on the totem pole” was a bold, probably rebellious, and almost inane decision. The then 18 year–old Katabi was as stubborn as she is today and always curious. She is a researcher.

“I always loved math,” she said. Electrical engineering is effectively applied math. The decision was a no-brainer. In 1997, after earning her degree in electrical engineering in Damascus, Katabi applied for graduate studies at MIT. “When I got acceptance from MIT, I was really surprised,” she admitted. “I think they had probably never seen anyone, at least in my department, coming directly from the University of Damascus.”

تميَّز عصر شبكة الويب العالمية بالنمو السريع، مع دخول عديد من المستخدمين الجدد إلى الإنترنت والتقدم الكبير في تقنيات الإنترنت والبنية الأساسية، ولكن أيضاً بعديد من المشكلات. أدركت القتابي أن أحد أكبر التحديات كان التحكم في حركة المرور على الإنترنت لتحقيق أقصى قدر من الكفاءة، فقررت التركيز في الدكتوراه على التحكم في ازدحام الإنترنت. طورت طرقاً أكثر ذكاءً لإدارة حركة مرور بيانات الإنترنت. على سبيل المثال أنشأت لاحقاً بروتوكول التحكم الصريح (XCP)، وهو بروتوكول للتحكم في الازدحام يوفر ملاحظات واضحة حول مستويات حركة المرور على الإنترنت، مما يسمح بتدفق البيانات بسلاسة أكبر. بعد الانتهاء من الدكتوراه، تقدمت بطلب للحصول على وظيفة أستاذة.

“I got offers from almost every place I interviewed: Berkeley, Stanford, MIT, as well as many others,” she said. She eventually decided to stay at MIT: “It was more of an emotional decision. I was young, and my friends were there my whole life,” she said. So far, it has suited her well. Her MIT projects demonstrate a powerful intersection of AI, wireless technology, and healthcare, paving the way for the future potential of AI in medicine. Her dream is to create AI models that continuously monitor physiological signals and predict health issues before they become critical. “Imagine if we could use non-invasive methods to monitor and predict health conditions, significantly improving people's lives,” Katabi said. In the future, we can have our own personal health guardians. A device can continuously monitor our physiological signals and feed them into an AI system to predict health issues. “To give you an example, subtle changes in a person's physiological data could help the AI detect early signs of Alzheimer's, allowing for timely intervention before the disease progresses significantly,” Katabi said.

In Massachusetts, the Syrian electrical engineer has found a way to fuse her background in computer science with her family’s medical heritage. “My parents are very happy,” she said. “My dad, a cardiologist, loves that I'm connecting engineering with medicine,” Katabi cannot stop stressing. However, her journey was not always a walk in the park.

“As a woman in engineering, especially coming from Syria, I had to prove myself at every step,” she reflected. “On the one hand, there was this cocoon around me of people who were very supportive and helpful and believed in science. On the other, there was adversity that made me always motivated to prove myself and do better.” Being in a bigger environment, where you are challenged all the time and women are not given equal opportunities, makes you stronger, she believed. “Life is not simple or easy,” she said. Katabi acknowledges that what she perceives as uncomfortable truths may have facilitated her success. “Most people think that I'm European or look at me as if I am. I don’t look particularly different from the people at MIT or in the US. But I think if someone had darker skin or looked different, they might have had a different experience,” she said. “Also, the perception of what I should or shouldn’t be doing could have been completely different if I was a medical doctor working with lay people on the street,” she swiftly added. Thankfully, the MIT ecosystem is pragmatic and results oriented: “People are scientists. They are logical, and not bound by these stereotypes.” Accomplishments are what matters.

Katabi received the MacArthur Fellowship for her innovative work in wireless data transmission and network management in 2013 and the ACM Prize in Computing for her groundbreaking contributions to network congestion control and wireless health monitoring in 2017, among others. Recently, she learned that she is an awardee of the prestigious 2023 Kuwait Prize for Applied Sciences. This award holds a special emotional connection for her. “It feels great to be recognized by my people,” she said. “It's not just a professional honor, but an emotional one as well.” Her parents are elated: the Arab world is recognizing their daughter, she said.

Katabi’s journey from Damascus to MIT is a powerful example of how belief in science coupled with sheer determination and single-minded determination can lead to groundbreaking innovations with the potential to improve lives worldwide. Her success might have come at the cost of free time, of which she has nil, but come to think about it, it was not a big sacrifice. “My work is my hobby,” she said. “It's something I enjoy, and I continue to enjoy it every day.”