Science education typically follows a rigid pattern. Students are provided with small facts and general principles, or simple theorems that explain the nature of our world. As students age, they progress into minor experimentation that unlocks new facts and principles or enter a science-related field that takes their understanding to new heights.

However, there is a critical element missing from this pedagogy — a concept that Fouad Abd-El-Khalick refers to as the nature of science.

“The nature of science is looking beyond the knowledge and beyond the process,” said Abd-El-Khalick, the dean of the School of Education at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “What we really need to be teaching in schools is how we develop scientific knowledge, the core values and characteristics of science learning, and why scientists do what they do; particularly why we should trust them.”

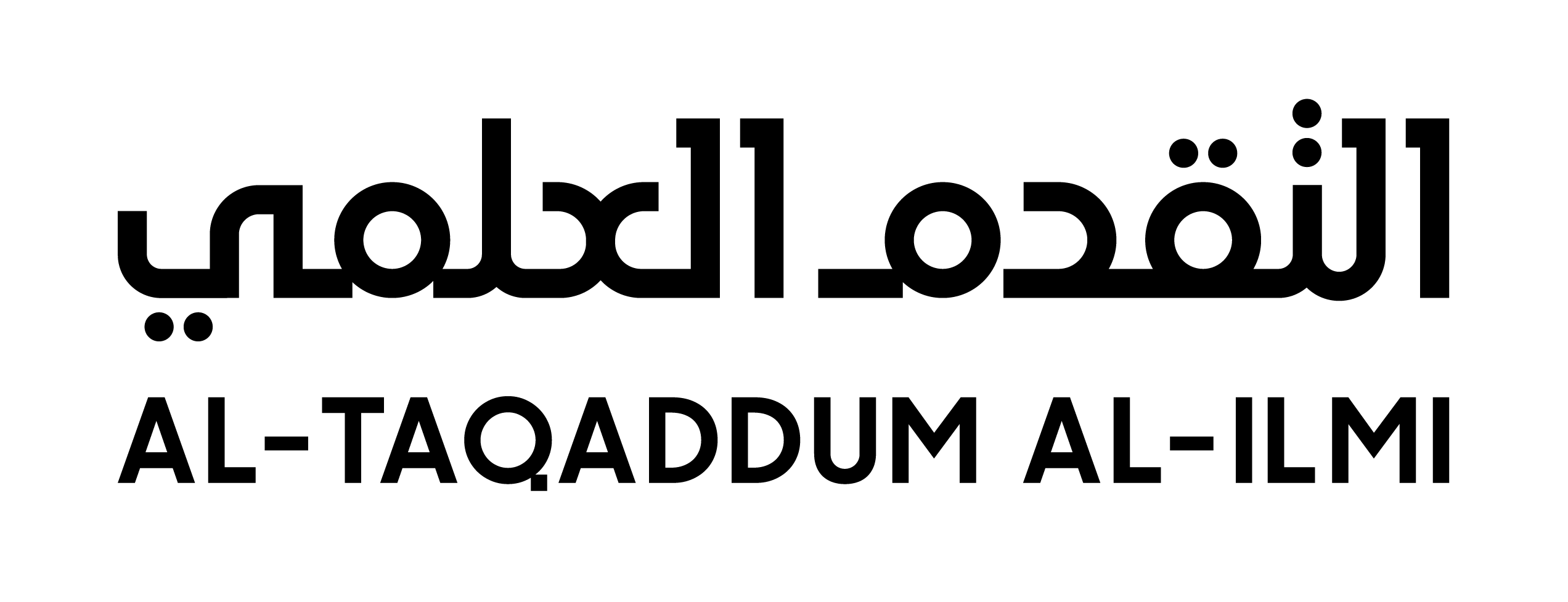

Abd-El-Khalick has been investigating the metacognition of science for more than twenty years. Growing up in Lebanon and attending American University of Beirut, he took an early interest in the modality of science education and traveled to the University of Oregon to complete his doctorate. Abd-El-Khalick wanted more opportunities to explore his field in greater detail, and in 2000, he permanently moved to the United States to pursue research through grant funding.

It wasn’t long before he received recognition for his work. To date, Abd-El-Khalick has received dozens of awards from institutions all over the country and is recognized as one of the world’s top researchers for metacognition in the field of science. His proudest achievements include the JRST Award, the NARST Distinguished Contributions to Science Education through Research award, and the 2021 Kuwait Prize from the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences (KFAS) for career accomplishments in the field of Economic and Social Sciences — Educational Sciences.

إن تدريس طبيعة العلم أمر مهم على نحو لا يُصدق. إنه يهدف إلى خلق الثقة في العلم بناءً على توعية الطلبة بالكيفية التي يعمل بها العلم بدلاً من مجرد معرفة الحقائق والفرضيات. ونحن في هذه الأيام نحتاج إلى ذلك أكثر من أي وقت مضى

يرى عـبد الخـالق أن جـائزة الـكـويت التي تقدمها Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences هي جائزة ذات رؤية تجذب الاهتمام الذي تشتد الحاجة إليه للباحثين في الجانب التقني لتعليم العلـوم. وقال: “أنا سعيد لأن مؤسسة الكويت للتـقدم العلمي تعـمل مع آخرين لتسليط الضوء على هذه الأعمال. أنا فخور جدًا بهذه الجـائـزة وبتراثي. إنه لأمر رائع أن أستمر في التعـامل مع بلدي وأن يكون لي بعض التأثير هنا وهناك”.

It’s best to think of Abd-El-Khalick’s research as the substructure of science. He does not focus on the products of science, which introduce students to theories, principles, or ideas. Instead, he focuses on the nature of science — teaching students how to develop scientific knowledge in the first place. Abd-El-Khalick believes the nature of science is not taught to students in K — 12 or early college classes and he aims to create a more complete understanding of science as learners progress through school.

“We just don’t teach the nature of science as a concept,” Abd-El-Khalick said. “We get everyone to memorize facts in order to reach some kind of knowledge, but neglect to show the whole host of things required to create a scientific idea.”

Take COVID-19, for example. “No single person could learn all the science necessary to make informed judgements about the pandemic,” he said. “Virology and epidemiology are all very complex, and the general population is not going to understand all these factors at once. If we just had a rounded education in the sciences, even for non-majors, we would have seen a very different response to the pandemic.”

Abd-El-Khalick points to poor education on the nature of science as one of the biggest factors impacting the 2020 pandemic response.

“It was easy for people to dismiss scientific claims, since many people did not understand which sources they should trust to make decisions,” he said. “The devastating part is that hundreds of thousands of lives could have been saved if people had trusted the nature of science.”

It’s clear that something needs to change in our current scientific pedagogy. Unfortunately, shifting the way science is taught in schools will be an uphill battle.

“We now know how current education gets people to think about scientific knowledge,” Abd-El-Khalick said. “It’s just not commonly practiced.”

What’s keeping teachers from weaving the nature of science into the classroom? Historical vacillation.

“The U.S. realized it wasn’t scientifically competitive after Sputnik, so we built and prepared for more scientists in the 1960s,” Abd-El-Khalick said. “However, we are now preparing graduates to function in a world that is increasingly technologically and scientifically laden. Somehow, we have been vacillating between periods of scientific preparation and periods of creating smart consumers of science; and never both.”

The world is slowly awakening to the importance of scientific pedagogy. However, progress is slow. Many classrooms still teach the process or products of science rather than its nature, and heavily rely on language, facts, and theories to educate learners. Unfortunately, this still misses the mark.

“Science is way more complicated than just the scientific method,” Abd-El-Khalick said. “It doesn’t start with an observation. It starts with an idea or theory — which is exactly what the nature of science teaches.”

Abd-El-Khalick is determined to see the nature of science reach classrooms in the U.S. and beyond. He plans to continue researching the metacognition of science in more effective modalities, and help students leave school with a robust understanding of how to think about science and make better decisions about the world in which we live.

“It is so unbelievably important to teach the nature of science,” he said. “It aims to produce trust in science based on educating students about how science works rather than just the facts and hypothesis. And these days, we need that more than ever.”