Saїd Yaktine: A Writer and Literary Critic

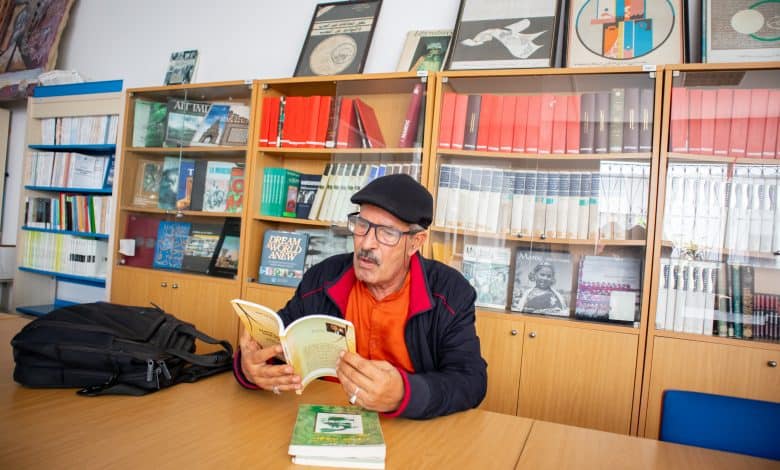

The Arabic word for literature is Adab. In just three letters [in Arabic], Adab encompasses a constellation of virtues, such as etiquette, manners, knowledge, wisdom, and self-cultivation. Arabic literature is rich and diverse, spanning some 16 centuries. Between the sixth and seventh centuries CE, it took the form of Pre-Islamic Poetry, celebrating tribal heroes and love. The Islamic Golden Age that followed, lasting until the 13th century CE, saw an unprecedented flourishing of poetry, prose, and scientific literature, playing a crucial role in preserving and disseminating Greek and Roman works. More recently, themes of identity, migration, and the challenges of living in the Arab world have dominated Modern Arabic Literature since the 1800s. A proud representative of Arabic Literature today is Saїd Yaktine, professor of higher education at the Faculty of Arts and Humanities at Mohammed V University in Rabat.

Born in Casablanca, Morocco, in 1955, Yaktine's journey to obtaining a state doctorate in Arabic literature from Mohammed V University in 1997 was marked by years of study and awards. He received his bachelor’s degree from the Faculty of Literature and Humanities at Mohamed Ibn Abdellah University in Fez. During this period, he was heavily influenced by the sociological studies of literature by Lucien Goldmann, a French philosopher and sociologist associated with structuralist and Marxist intellectual traditions. Eventually, Yaktine chose to concentrate on narratology—the study of how narratives work, are structured, and function in literature, film, oral storytelling, and other media—drawing on the theory of Gérard Genette, a French literary theorist who laid the foundation for the systematic study of narrative structures and techniques. In 1981, Yaktine received a certificate of completion of studies from Rabat, specializing in the novel, and soon registered the subject of a thesis for a diploma in postgraduate studies on the sociology of the Arabic novel. In 1983, he joined a university teaching training scheme, and after two years of academic formation, he joined the Faculty of Literature and Humanities–Ben M'sik in Casablanca. In 1985, Yaktine re-registered the same thesis, with the goal of completing and defending it by 1988. That same year, the Faculty of Arts at Mohammed V University in Rabat invited him to join as an academic member.

In 1989, Yaktine won one of his first major awards, the highest Moroccan Prize for Literature, a feat he repeated in 1997. In 1990, he registered his doctoral thesis on Arabic Popular Sirat (popular biography), defending it in 1997. This work led to the publication of two books: Speech and Narrative: An Introduction to the Arab Narrative and The Narrator Said: Storytelling Structures in Folk Biography, both released in 1997. In 2016, Yaktine was awarded the Sheikh Zayed Book Award in the Literary and Art Criticism category for Al-Fikr al-Adabi al-‘Arabi (Arabic Literary Thought), and in 2022, he received the Katara Prize in Narrative Criticism for Narratology in Practice. Most recently, he has added the Kuwait Prize in Humanities, Arts, and Letters from the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences (KFAS) to his accolades.

Unlike many of his peers, Yaktine did not study abroad—largely due to personal choice and circumstance. “I thought about it after graduating from high school, but my family’s financial circumstances did not allow it,” Yaktine explained. Additionally, his family had no idea he aspired to study narratology. After completing his high school diploma, Yaktine joined the regional center for teacher formation, and after two years of training, he worked as a preparatory education teacher, allowing him to continue his university studies. That said, between 2002 and 2004, he taught narratology as a visiting professor at Jean Moulin University Lyon 3 in France. “But I did not want to join this university permanently because I believe my place is in my own country, not abroad,” Yaktine said.

Yaktine’s publishing record is extensive, with 13 papers published in peer-reviewed journals, 13 papers in book chapters, and 19 books. His favorite themes include ancient Arab narratives, literary theory, literary criticism, Arab-Islamic narrative heritage, and popular culture—topics he believes resonate more profoundly when one is living in an Arab country.

Modern Arabic narrative is a fascinating and complex intellectual hybrid. “It retains many elements from ancient narratives in terms of language, techniques, and eloquence—just look at A Thousand and One Nights, the iconic collection of Middle Eastern folktales and stories compiled over centuries—but it also incorporates Western narrative trends in the short story, novel, and play,” Yaktine said.

He added that modern Arab writers are products of the realities Arabs have faced since colonialism, which divided the Arab world and its countries. “All the regimes that came after independence were subject to neo-colonialism, which imposed its agenda,” he noted. In this cultural landscape, Arab writers are deeply invested in the social, political, and cultural conflicts surrounding them. Issues of identity, immigration, love, and political conflict are central to the literary discussion, with few modern Arab novels omitting them. Yaktine, however, believes the issue of freedom of expression may have been overstated, at least when it comes to the novel. “Despite what is said about freedom of expression in the Arab world, the novels that have suffered from bans are very few throughout modern Arab history,” he said.

As for the spread of the Arabic novel to the rest of the world so that non-Arab readers could learn more about the distinct cultural, historical, and linguistic heritage of the Arab world and identify with the universal themes of identity, exile, and the clash of tradition and modernity at its core and marvel at the extensive use of metaphor and symbolism Adab is rich in? “Translation can play an important role in making Arabic literature accessible to readers worldwide,” he said. “Teaching Arabic literature in Western universities is also important for fostering rapprochement between peoples and bridging the gap between East and West.” He also advocates for the exchange of visits between Arab and foreign writers and for translating Arabic critical studies to bridge viewpoints—so long as this is done with an open mind, not to reinforce biases or prejudices. “Some foreign researchers study Arabic literature ideologically, focusing only on texts that appeal to them or that present negative images of Arabs,” Yaktine remarked.

Currently, Yaktine is finalizing two books: Historical Cultural Identity and Achieving the Manuscript of “The Sword of Crowns,” which he describes as an unknown folk biography—one of several books he intends to publish in the future. He is also editor-in-chief of The Other Culture, a magazine that focuses on Moroccan popular culture. “I am constantly working on all the topics that interest me—ancient and modern Arabic narratives, Arab popular culture, digital culture, and socio-cultural analysis,” he said. He finds it hard to single out any particular work.

“I always start from the same conceptual framework—narrative analysis,” Yaktine said. “In a sense, each subsequent work relates to and is linked with the previous one.”

By Stav Dimitropoulos